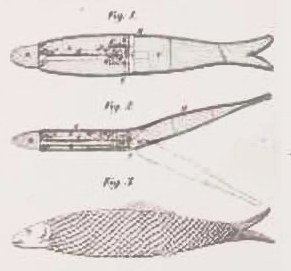

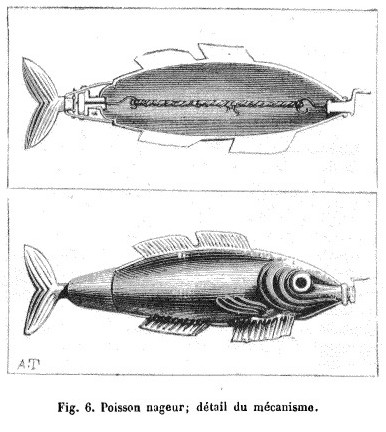

In his early days of an toy manufacturer Fernand Martin invented a mechanism with a rubber band (elastic) as the drive.

He used his invention on his first piece: the fish (Poisson Nageur) but he discovered that another manufacturer Mr. Fournier used his invention and the Richard brothers sell these toys.

July 5, 1884.

Lawsuit: Fernand Martin versus Mr. Fournier and the Richard brothers.

Mr. Fernand Martin had patented a drive system for children’s toys.

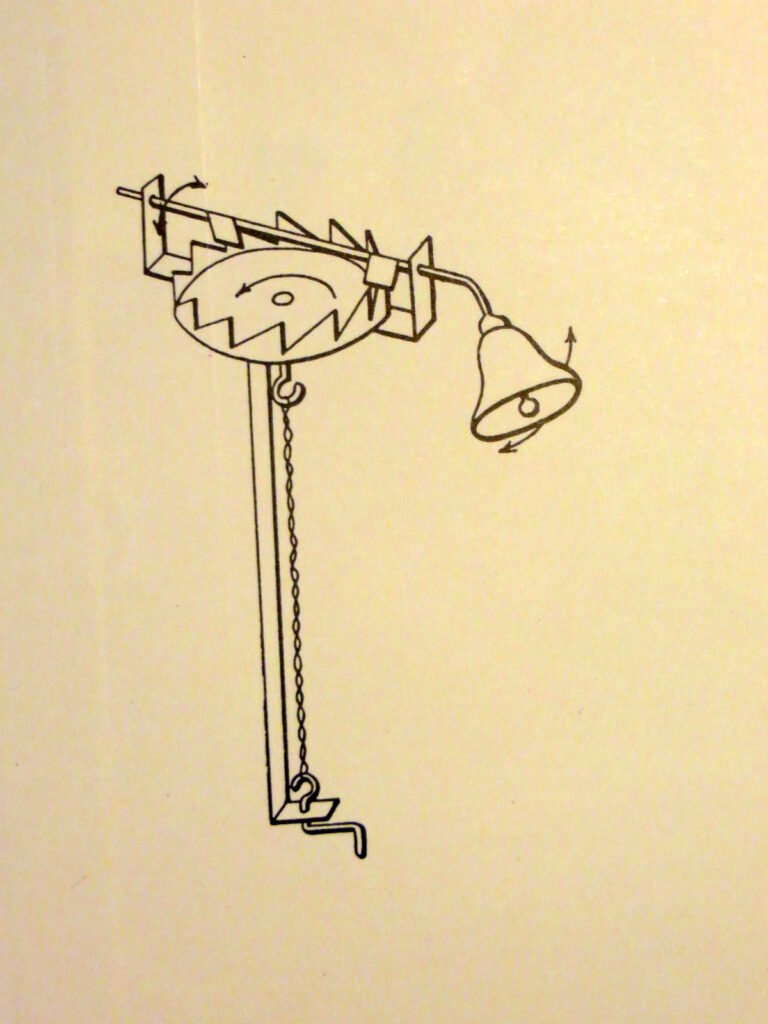

The mechanism consisted of a twisted rubber, intended to turn an eccentric, this successively touched the two prongs of a fork on which he pressed thus made a reciprocating movement, transmitted to the moving part of the toy.

A few days after taking out his patent and without having used it yet, Mr. Fernand Martin discovered an improvement for which he obtained a certificate of addition, which consisted in replacing the eccentric with a gear that acted on the fork, which had the advantage that the number of movements increased significantly.

Mr. Fournier and the Richard brothers claimed that the patented system was already known and after selling toys equipped with a mechanism identical to Martin’s patent, Fernand Martin sued them for counterfeiting in the criminal court of the Seine; the case was referred back to the 10th Chamber on February 6, 1883 and pronounced the following verdict:

After deliberating in accordance with the law.

While Mr. Martin took out a patent on January 14, 1879 to retain exclusive ownership of a propulsion system applicable to children’s toys and especially originally to so-called fishes.

The mechanism he uses to operate his toy consists of three different parts: a twisted rubber band, an eccentric hook, and a fork that is later referred to as the mechanism’s anchor. While this fork plays an important part in the combination of the various parts of the device, it does not exist in the toys previously manufactured according to the patented models of the Société Dandrieux, Gravier et Cie. and the gentleman Mancelin and Duval.

While the description in Martin’s patent shows that the rubber band, returning on itself after undergoing extreme torsion in its movement, takes with it the hook which successively touches the two small tabs, of which the fork or escape anchor to which the tail of the fish is attached and meanwhile moving it back and forth, these beats work from right to left, he works like a roer and produces a forward action. While Martin has obtained propulsion motion through the arrangement of various organs; that he succeeded in putting together an industrial product through the new application of known means. While he has adapted his system to different toys such as boats, swings and others; that, in order to increase the swings of the fork, he replaced the rod with a gear, as evidenced by the certificates of additions and improvements dated February 18 and June 25, 1880, duly taken, while Fournier does not dispute not the manufacture of toys to whereupon he modified the mechanism assembled by Mr. Martin, contenting himself with claiming that the device was not patentable.

While it follows from the confessions of the Richard brothers Ciné and Jeune that they offered and sold toys manufactured by Fournier, knowing that they were counterfeit.

Considering that the tools mentioned in the minutes of Mr. Signorat, judicial officer in Paris, dated December 21, 1882, were wrongly seized.

Whereas the forgery of which Mr. Martin has caused him lifelong damage for which he must be compensated.

The court has sufficient evidence to determine the amount of damages to be awarded.

For these reasons:

Does the court sentence Mr. Fournier and the two Richard brothers jointly and severally to a fine of 100 francs,

Orders them to pay Mr. Martin, namely: Mr. Fournier an amount of 1000 francs and the brothers Richard each to an amount of 500 francs as compensation and also condemns all three to the which ones advanced by Mr. Martin, civil party, to the amount of 43 Fr. 50 and orders the confiscation of the said objects and their delivery to Mr. Martin.

Source Gallica: Annales de la Propriété Industrielle Artistique et Littéraire Jan. 01-1885